Below is the first in a series of blog posts by this year’s Ferrar prints conservation intern, Thomas Bower, who has completed the project following on from the work of last year’s intern Puneeta Sharma.

I was very lucky to be selected as this year’s conservation intern for the Ferrar Project in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College Cambridge. Throughout August I conserved and re-housed around 260 prints collected by Nicholas Ferrar, a seventeenth century businessman. The work involved cleaning and repairing the prints before re-housing them in new folders to help preserve them and enable easier, safer access to the collection by scholars and the general public.

Working with the prints provided a wonderful opportunity to examine them closely. This examination revealed interesting details about early modern papermaking and the prints’ subsequent history.

Papermaking machines were not developed until the early years of the Industrial Revolution, so the paper on which Nicholas Ferrar’s prints were produced is all handmade. Papermaking in the early modern era was a highly skilled craft requiring a team of workers operating in careful collaboration. The basis of paper is cellulose, which can be obtained from various organic materials. Today the main source is trees but most early modern European paper was made from cotton and linen rags, which were beaten in water to produce a vat of fibrous pulp. It was difficult to filter the pulp and it often ended up containing impurities that were transferred to the paper, such as human hairs or small shards of metal that rust over time (Fig. 1).

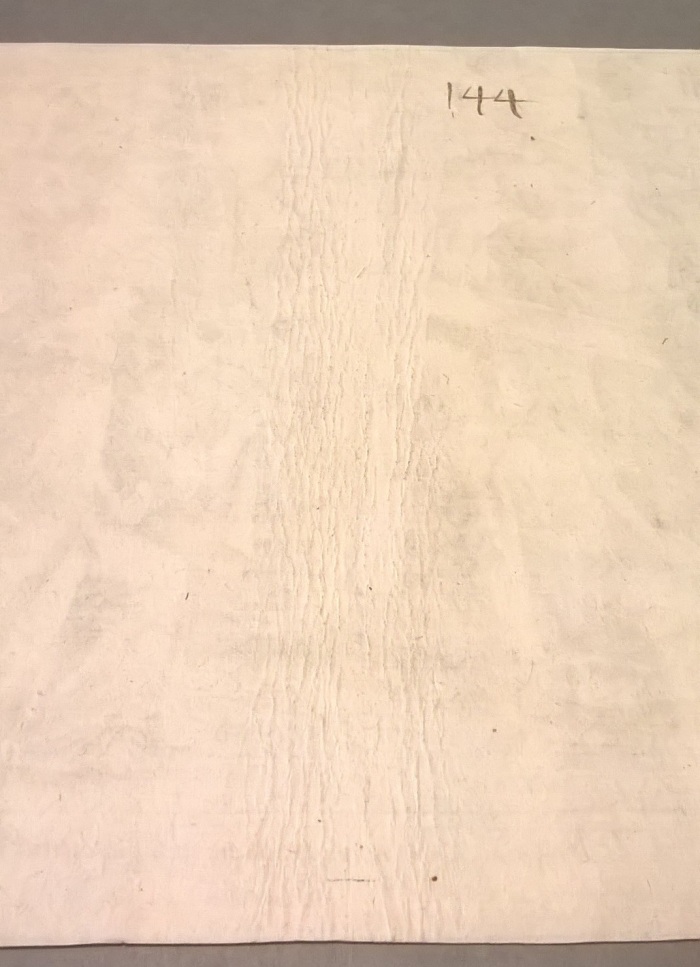

To produce a sheet of paper, papermakers lifted pulp from the vat using a papermaking mould – a flat wire mesh in a wooden frame. The water from the pulp drained away through the mesh, leaving behind a damp sheet of matted fibres. The outline of the mesh wires (known as chain and laid lines) remains in the paper and can be seen when light is shone through it (Fig. 2).

Many of the prints also have watermarks – symbols created in the mesh using pieces of wire, which papermakers used as their ‘logos’ (Fig. 3). Once the new sheet was removed from the mould it was placed between felts and pressed to remove excess water before being hung over ropes in a loft to dry further. Many of the prints show indentations in the paper left by the rope on which it was dried (Fig. 4).

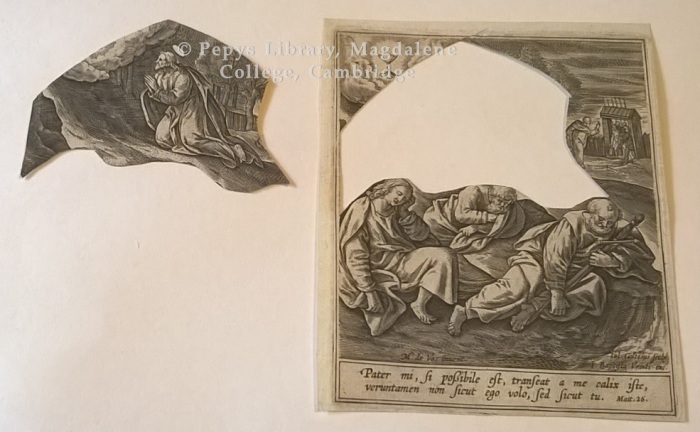

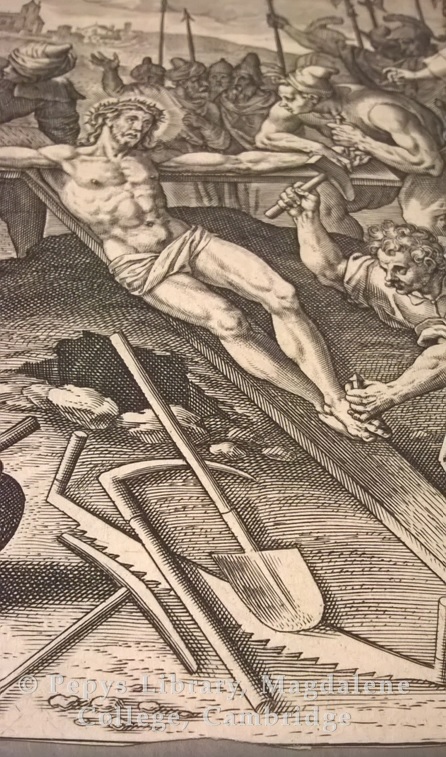

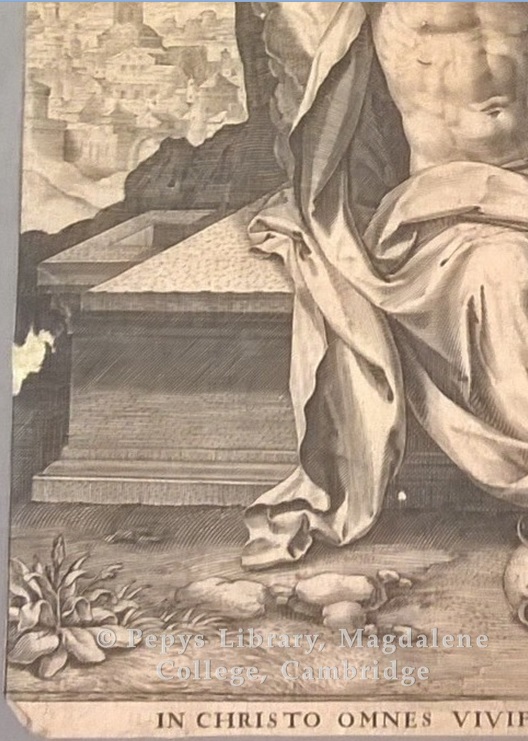

The Ferrar collection has an interesting history, which close observation of the prints helps to reveal. The prints were collected by Nicholas Ferrar when he was travelling in Europe during the early seventeenth century. The majority illustrate stories from the Bible, although there are also prints based on classical mythology and portraying different trades of the day such as printmaking and alcohol production. Once they arrived in England the prints were not left pristine and untouched. The Ferrar children cut out sections of the prints in order to produce a ‘Harmony of the Gospels’ – a scrapbook depicting biblical stories (Fig. 5).

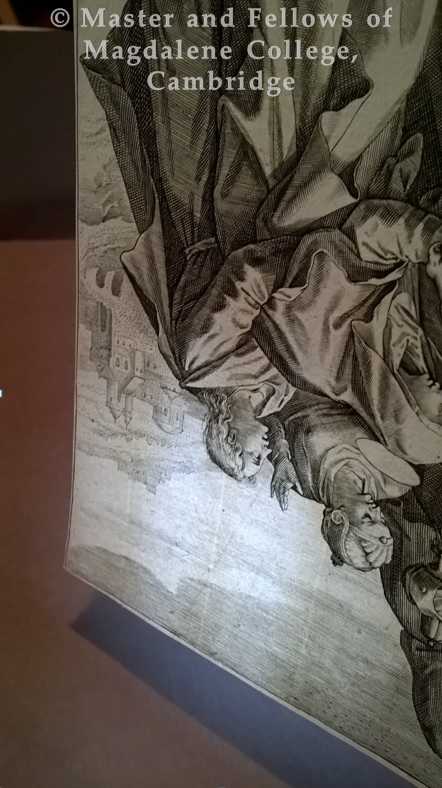

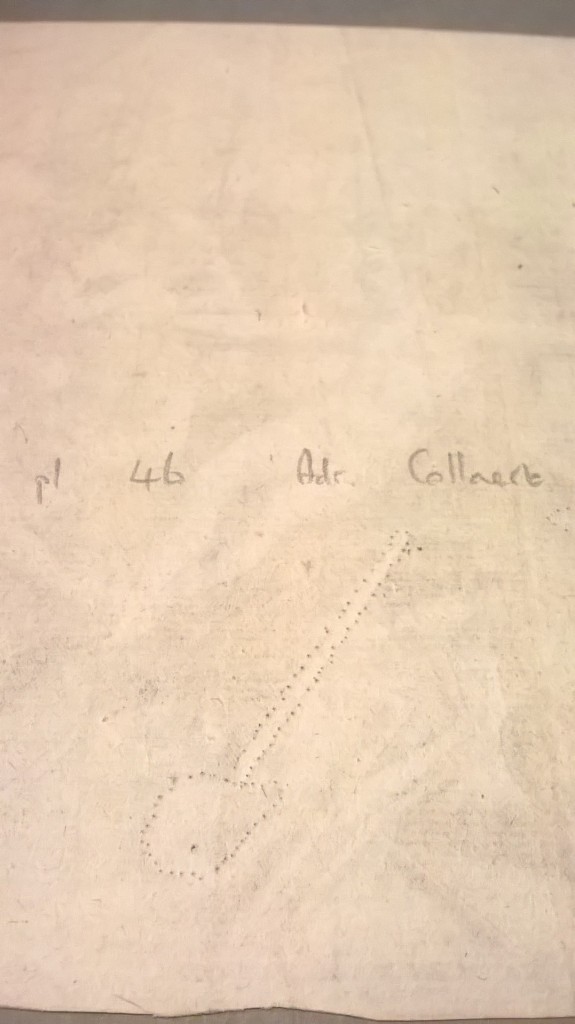

It seems one of the prints may have been used to transfer an outline of an image onto another surface (Fig. 6-7). A missing piece of another print has been infilled using another piece of paper (Fig. 8).

It is amazing what can be revealed by simply taking time to look closely at historic prints. I recommend visiting the Pepys Library to explore the Ferrar prints and other treasures from the collection!

By Thomas Bower

Ferrar Prints Conservation Intern 2015