At Thomas Hardy’s funeral in Westminster Abbey on 16 January 1928, the pallbearers included the Prime Minister (Ramsay MacDonald) and the leader of the opposition. They were supported by Rudyard Kipling, Edmund Gosse, George Bernard Shaw, J M Barrie and John Galsworthy, and also by the Master of Magdalene College Cambridge, where Hardy had been a much respected Honorary Fellow. Hardy, already a famous novelist and poet and recipient of the order of Merit (1910), had been introduced to Magdalene by the Master A C Benson and was admitted to his Honorary Fellowship in 1913.

Oil Painting of Thomas Hardy in the College’s collection of art, by R.E. Fuller Maitland.

When he died, Hardy left to Magdalene a manuscript in his distinctive hand, containing the great poetry collection Moments of Vision. After some confusion on the part of the executors, who initially sent a single poem, the whole manuscript arrived in the College according to his instructions.

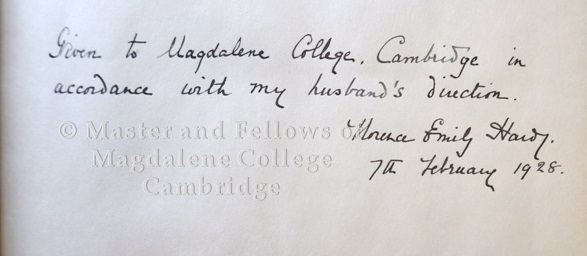

Inscription in the Magdalene Hardy Manuscript.

In a letter to accompany the bequest, which is now kept with the manuscript, his widow commented on the enormous affection Hardy had for the College, where he had visited often over many years.

The Letter from Hardy’s widow, accompanying the bequest of the manuscript of ‘Moments of Vision’.

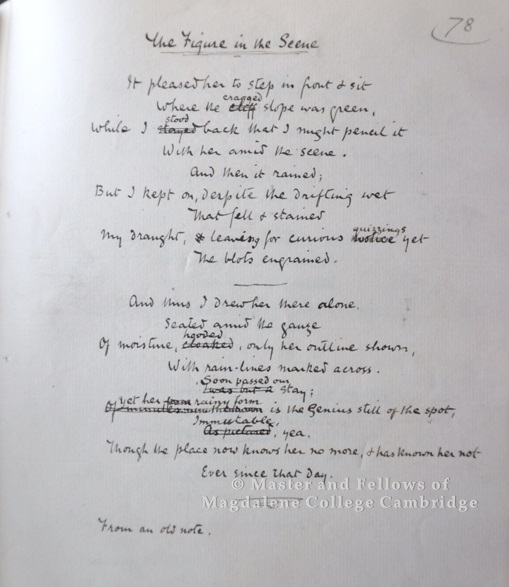

The manuscript is a superb resource for those interested in Hardy’s working practices. Many of the poems show corrections and changes as the poet chose with precision the right words and phrases. In the example of ‘The Figure in the Scene’ (picture below), we can observe the delicate and thoughtful revisions to a poem inspired by the poet’s sketching his first wife Emma at Beeny Cliff on 22 August 1870: the phrase he first wrote, ‘cliff slope’, is changed to ‘cragged slope’, which perhaps determinedly avoids the unintended reminder of other, more threatening, literary cliffs (such as Charlotte’s Smith’s ‘rough cliff’ frequented by a ‘lunatic’ or the suicidal Gloucester’s imagined cliff in King Lear). Or perhaps ‘cliff’ suggested a precipitousness which contradicts the more forgiving ‘slope’. The poet — not ‘staying back’ as originally written, but now standing back, adopting a fixed position from which to observe the scene — draws the figure sitting on the slope, ignoring the falling rain: ‘But I kept on, despite the drifting wet/That fell & stained/ My draught, leaving for curious notice yet/The blots engrained’. On reflection, Hardy deletes the word ‘notice’ and replaces it with the very unusual and suggestive ‘quizzings’. Under revision, the ‘cloaked’ figure becomes instead ‘hooded’, now no longer susceptible to identification. The archaic poetic phrase ‘’Twas but a stay’ becomes more straightforwardly ‘Soon passed our stay’, which subtly uses the pronoun ‘our’ to bring the poet back from his distant observation of the lone figure into a more conventional connection with his wife: the couple out for a trip to the cliffs. Most strikingly, the substantial and multiple revisions in line 6 of stanza two appear to alter the point of the poem: the idea of a momentary scene caught by the pencil of the artist is replaced by a transcendent idea (echoing Byron’s words on the eternal city, Rome) of the figure still occupying the landscape after the moment is gone: the figure is ‘immutable’ as the ‘Genius’ (i.e. spirit) of the spot.

‘The Figure in the Scene’ from the Magdalene Hardy Manuscript.

The critic Tom Paulin calls ‘The Figure in the Scene’ ‘an unremarkable poem’, but knowledge of the process of composition revealed in the Magdalene manuscript adds a new dimension.

Dr M E J Hughes (Pepys Librarian)

We invited Dr Heather Brink-Roby, Junior Research Fellow in English who has written a PhD on Hardy, to contribute this guest post in which she reflects on the value and the power of examining the original ‘holograph’ manuscript of Thomas Hardy’s Moments of Vision.

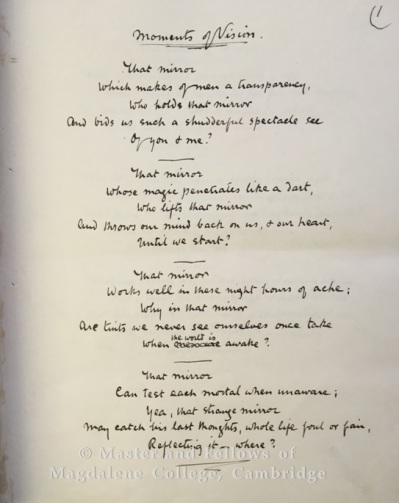

Why do we read manuscripts of published works; what is the peculiar allure of that often onerous experience? And why should we read the holograph manuscript of Thomas Hardy’s poetry collection Moments of Vision, which he left to the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he was an Honorary Fellow?

A fragrant flower pinned to a coat on a cold day seems to revive in the human warmth of its wearer, even as that person walks along transported perhaps in the atmosphere of the flower’s scent. There is something of this symbiosis in a manuscript’s relation to its reader. The reader revives the process of writing, and in doing so, the writer is more present, more localized. The manuscript seems to offer the prospect that that we can enter into a newly definite relationship to the writer: whether to to approach or shun him or her, whether to gain new distance or new intimacy with the poem.

Among the primary concerns of Hardy’s volume, which gives its writer physical presence, are the material intimations of lost persons (who are not regained but newly present as lost): the moth beating against the window pane (the soul nearby yet impossibly remote) in the poem “Something Tapped” ; or the face glimpsed just above the evening mist in “The Head above the Fog.” Ten of the poems are from 1912 (when Hardy’s wife Emma died) or the following year, and develop the elegiac tone later seen in Satires of Circumstance (1914); others recall his courtship and first years of marriage. The writing was not without cost to the poet: A.C. Benson’s diary for November 4, 1913 records Hardy, on his visit to Magdalene for admission as Honorary Fellow, speaking of his wife’s death and worrying that it was “indecent” to write poetry.

The creative intimation of ‘lostness’ is the very method of Moments of Vision.. Many of the poems had previously been sent to publishers who had declined them; lost, they had to be re-created by Hardy from notes. But the notes, too—in their fragmentariness—must themselves have stimulated Hardy’s imagination: broken and half-lost yet recalling him to memories of that time and those feelings when he first began to compose the poems.

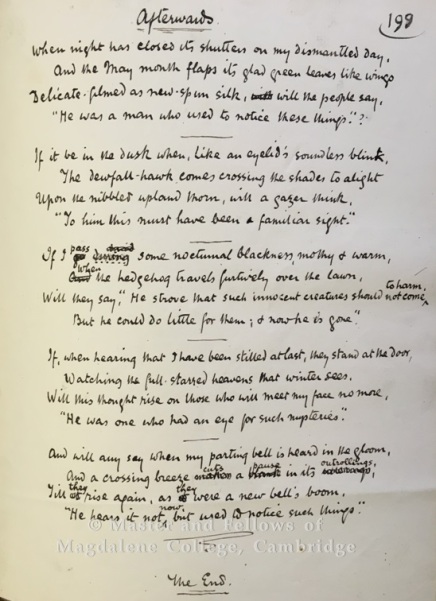

Moments of Vision is itself concerned with the overlooked: with minute details of nature, with that which has long been underground, with obscure persons, or with the stories behind homely objects. These poems wonder whether your ability to notice something that others do not reveals your affinity with that thing (the hedgehog moving across the night lawn); or whether it proves the presence in you of exceptional active powers of observation; or whether perhaps it implies a rare receptivity (a willingness to take in or harbour what others will not.

‘Afterwards’

Hardy is fascinated in these poems by ‘outwarding’, by moments in which something becomes available to sense. On the one hand, he experiments with poetry’s ability to objectify our inner life, render those presences that haunt us as spectres in the outward scene; in other words, he takes the subjective, interiority-focused literary tradition so far that it flips into its opposite: the objective or dramatic. On the other hand, he is concerned with those rare moments in which an outward scene suddenly lays bare to us our inner life, when we seem to gaze out into ourselves. We apprehend something in us, for the first time, through something outside us (the tradition of magical mirrors that can present remote scenes presumably arises from a mirror’s routine ability to image the otherwise invisible, our own face).

‘Moments of Vision’

Thus attuned to the idea of observing the over-looked, the reader cannot help but attend suddenly to the poet’s handwriting itself. We feel poignancy in the backward-yearning stem of the letter ‘d’; we attend to a place where the lightening ink grows abruptly black – perhaps expressive of a state of emotional exhaustion, a hesitation that seemed to demand a renewal.

Charles Lamb wrote of the experience of viewing Milton’s Lycidas manuscript in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge, “how it staggered me to see the fine things in their ore! interlined, corrected! as if their words were mortal, alterable, displaceable at pleasure! as if they might have been otherwise, and just as good! as if inspiration were made up of parts…!” Similarly, in Hardy’s holograph we are aware of the parts of the poetry: stanzas are added, words are substituted, lines are re-written, and even the sequence of poems is changed – the table of contents shows that “Signs and Tokens” was first placed where we now find “The Five Students,” for example.

Stanza added in ‘The Glimpse’

But the manuscript is perhaps most helpful in giving us a sense of Hardy’s movement of thought. The Clarendon Edition of Moments of Vision includes Hardy’s alterations, but it simply lists them (in footnotes) in the order in which they appear in the finished poems. The manuscript, by contrast, often makes obvious the actual order in which changes were made. In the final line of “During Wind and Rain,” for example, we see how introducing “ploughs” ultimately elicited a change from “chiseled” to the more unified “carved.” So, “On their chiseled names the lichen grows” becomes, only in stages, “Down their carved names the rain-drop ploughs.” Hardy shifts the image from a familiar one of time’s obliterations of personal identities to that of the channeled and channeling: an intimation of the ambivalent processes of memory by which sharp details are lost even as contours are more deeply insculped.

‘During Wind and Rain’

Hardy wrote in his journal, “I do not expect much notice will be taken of these poems: they mortify the human sense of self-importance by showing, or suggesting, that human beings are of no matter or appreciable value in this nonchalant universe.” But for me the individual’s lack of matter becomes its affirmation; the filminess of persons, their delicate ephemerality, and our sense that they are cosmically underprized draws us newly, irresistibly to them.

Confronted with a manuscript, we sense at once a new immediacy and new mediation. On the one hand, there are no intervening persons, editors, typesetters, interpreters; on the other, the calligraphy—in its irregularity, beauty, and difficulty—is a physical presence that does not allow itself to be simply looked through. This material object renders the text itself, at once, as remote as another age and as close as our senses.

Perhaps part of what we ultimately seek in visiting an archive is in fact an enhanced acuteness in our relation to the poems: numerous possible experiences of Hardy’s writing (the many printed copies, recordings, critical readings) focused to a single one; and a totality of reading experience compressed to a few hours of contact.

Thomas Hardy’s entry in the Magdalene College Admissions Book, Magdalene College Archives B/442

Dr Heather Brink-Roby

Junior Research Fellow in English