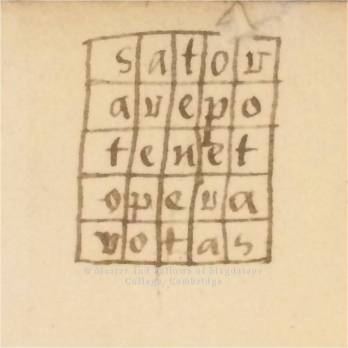

For this week’s Incunabula Season blog post, Ellie Swire discusses the handwritten ‘Sator Square’ discovered in an Old Library incunable.

The term ‘sator square’, or ‘rotas square’, is used to describe the particular arrangement of five Latin words – Sator Arepo Tenet Opera Rotas – into a 2D palindrome. A palindrome is a word, number, sentence or sequence which can be read the same way from left to right and from right to left. In 2D palindromes such sator squares, words can be read horizontally and vertically across their composite rows and columns:

SATOR ROTAS

AREPO OPERA

TENET TENET

OPERA AREPO

ROTAS SATOR

The earliest archaeological evidence for the use of sator squares has been dated to the 1st century A.D., in examples found in the ruins of the ancient Roman city of Pompeii in southern Italy, but to this day, scholars remain divided on the question of the sator square’s precise origin and purpose.

Translated into English, the words contained within the square form the sentence: “Farmer Arepo works his wheels / plough” – a straightforward enough expression which, on a superficial level, could be seen simply to fulfil the formal requirements of the palindrome as a clever word game in the absence of any underlying ‘hidden’ meaning. Contrasting interpretations of the square which focus on its concealed mythic and religious associations, however, have ensured that the symbolic significance of the sator square remains a source of continued academic interest. Among its many various manifestations from the 6th century onwards, the sator square has, for instance, held an important function as a magical charm, used to cure sickness, avert disaster and protect against evil spirits.

Another strong vein of research in the history of sator squares has concentrated on establishing a link between the square and early Christianity. This tradition identifies the farmer / sower figure ‘Arepo’ with Christ and argues for the re-appropriation of the sator square by as a covert religious symbol by Christians during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. By rearranging the letters contained within the square into an anagram in the shape of the Christian Cross, in which the words “Pater Noster” form the vertical and horizontal beams and the remaining A/O letters appear adjacent to the Cross as representative characters for the Greek Alpha and Omega, the “beginning and the end”, the sator square forms a powerful Christian cryptogram, easily disguised from non-Christians.

P

A

ATO

E

R

PATERNOSTER

O

S

ATO

E

R

Other theories reject this Christian interpretation in favour of possible Jewish, Mithraic or ancient Greek sources. Whatever their derivation, examples uncovered throughout Europe and beyond indicate the enduring appeal and repurposing of sator squares across shifting geographical and cultural boundaries.

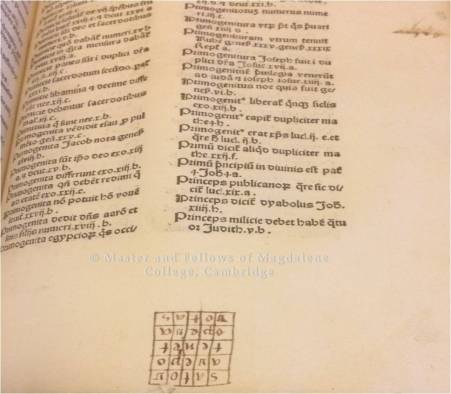

Old Library F.3.21: Tabula in libros Veteris ac Novi Testamenti Nicolai de Lyra. [Cologne: Johann Koelhoff, the Elder, not before 1480].

Close-up of the Sator Square

It is impossible to identify the author of the square with any certainty, though it is at least feasible that, had the square not already been added by a previous reader, it could have been added by the book’s earliest known owner, Thomas Nevile (1546-1615). Nevile was an English academic and clergyman, who served as Dean of Peterborough (1591-1597), Dean of Canterbury (1597-1615) and Master of Magdalene College (1582-1593).

By Ellie Swire

Libraries Assistant and Invigilator

Further reading

Baines, W. (1987) “The Rotas-Sator Square: a new investigation”. New Testament Studies. Vol. 33(3), p.p. 469-476.

Fishwick, D. (1964) “On the origin of the Rotas-Sator Square”. The Harvard Theological Review. Vol. 57(1), p.p. 39-53.

Sheldon, R.M. (2003) “The sator rebus: an unsolved cryptogram?” Cryptologia. Vol. 27(3), p.p. 233-287.

Someone created it. Then others saw it and copied it for their own reasons then others saw it and imbued it with their own ideas. And so it came to represent everything and nothing. A shiny pebble might represent something different or mysterious or historical to those whose hands it passes through. Likely created by a person who enjoyed word play and word games.