Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle

The Old Library of Magdalene College has a fine collection of works by Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. Cavendish (née Lucas) was born in 1623 at St. John’s Abbey, near Colchester in Essex. Like many other members of aristocratic royalist families in the 17th century, she went into exile (her brothers were prominent royalist officers during the English Civil War). Cavendish’s exile was an intriguing one: she became a maid of honour to Queen Henrietta Maria, and in 1644 travelled with the Queen to Paris, becoming part of the court of Louis XIV.

Margaret Cavendish was a prolific author. She wrote in a variety of subjects and genres, at a time when female authors were few and far between. Her closest English counterparts were Aphra Behn, Katherine Philips and Anne Finch, but Cavendish was the only author to be publishing works on science and natural philosophy.

Magdalene’s Old Library contains the following of Cavendish’s works: Orations of Divers Sorts (1662), Philosophical and Physical Opinions (1663), Philosophical Letters (1664), Poems and Phancies (1664) CCXI Sociable Letters (1664). Grounds of Natural Philosophy (2nd edition of 1668, originally conceived as a reworking of her Philosophical and physical opinions of 1663) and Plays never before printed (1668). All of the books by Cavendish in Magdalene’s collection are in ‘folio’ format, which was a deliberate choice by the author. Jagodzinski writes that this choice of format astounded Cavendish’s contemporaries, furthermore ‘had been traditionally been reserved for classical and theological works and had only recently been used for the works of lyric and dramatic poets..This writing woman appeared to overstep the gendered boundaries between public and private by publishing her work.’

Cavendish was also not afraid to critique writers such as Descartes and Hobbes in her Philosophical Letters. Perhaps to mitigate reaction to a female author engaging in public intellectual dispute, or to assert her place amongst philosophers of the time, she writes in the dedicatory passage to her husband:

Dedication page of Old Library C.3.12, Philosophical Letters (1664)

My Noble Lord, Although you have always encouraged me in my harmless pastime of writing, yet was I afraid that your Lordship would be angry with me for writing and publishing this book, by reason it is a book of controversies, of which I have heard your Lordship say…But your Lordship will be pleased to consider in my behalf, that it is impossible for one person to be of every one’s opinion…’

This is one of several examples of Cavendish using the prefatory material in her works to explain and justify their publication. On the one hand, she says in the preface to Plays never before printed that she is merely writing for her own pleasure, and is not concerned with how her work is received. She says of her books, ‘I write and disperse abroad, only for my own pleasure, and not to please others: being very indifferent, whether any body reads them or not; or being read, how they are esteem’d’

Dedication page of Old Library C.3.11, CCXI Sociable Letters (1664)

On the other hand, she mentions in CCXI Sociable Letters to take her sex and lack of formal education into account when reading her works, which implies that Cavendish did have a desire for a positive reception of her work: ‘I pray consider my sex and breeding, and they will fully excuse those faults which must unavoidably be found in my works. But although I have no learning, yet give me leave to admire it’.

Dedication page of Old Library C.3.10, Poems and Phancies (1664)

Even though Cavendish chooses to address mostly men or male dominated environments in her dedication pages, such as her husband, her brother-in-law or ‘The Universities in Europe’, she also justifies her choice of authorship to a female audience. In Poems and Phancies, she addresses ‘all noble and worthy ladies’ by beginning, ‘Condemn me not as a dishonour of your sex, for setting forth this work; for it is harmless and free from all dishonesty; I will not say from vanity: for that is so natural to our sex, as it were unnatural, not to be so.’

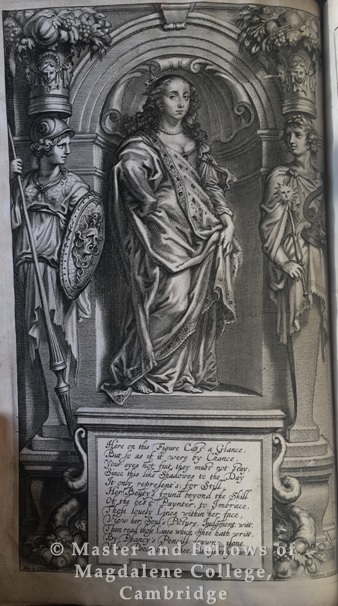

Engraved Title Page of Old Library C.3.8, Plays never before printed (1668)

The contradiction between the self confident remarks when introducing her writing and instances of setting a humble, almost apologetic tone are further highlighted by this impressive frontispiece engraving by Abraham van Diepenbeke, which two of Cavendish’s works housed at Magdalene include. Cavendish is dressed as a classical author, and as Jagodzinski describes, ‘barefooted, with more than a little décolletage, wearing an ermine-lined cloak, and crowned with a coronet which sits jauntily at the back of her head.’ The god of music and poetry, Apollo, is on her left, and the goddess of wisdom, Athena, is on Cavendish’s right in the engraving.

Magdalene’s most famous 17th century alumnus, Samuel Pepys, commented on Cavendish in both a social and scholarly context. Pepys talks at length of her visit to the Royal Society on the 30th May 1667. He says of the Duchess’ invitation to the Society meeting, ‘after much debate pro and con, it seems many being against it, and we do believe the town will be full of ballets [ballads] of it…After they had shown her many experiments, and she cried still she was “full of admiration,” she departed, being led out and in by several Lords that were there.’

By Catherine Sutherland

Deputy Librarian, Pepys Library and Special Collections

Bibliography

Jagodzinski, Cecile M. : Privacy and Print: Reading and Writing in Seventeenth-century England. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1999.

Latham, R. and Matthews, W. (eds) The diary of Samuel Pepys. London: Bell and Sons, 1974.